Intro // To Satirise, Must We First Imitate?

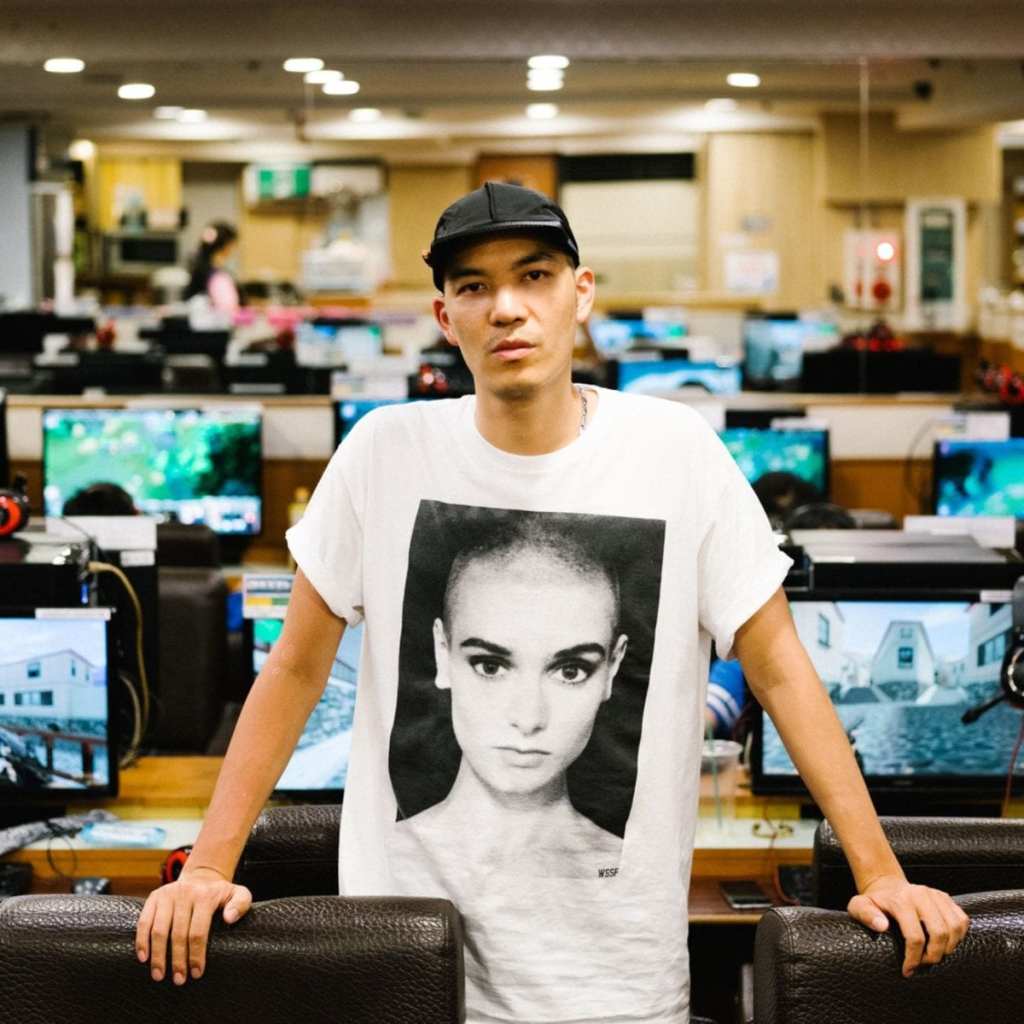

Tzusing is obsessed with masculinity. His music thrusts into a land of leather-slick nightclubs and digital testosterone. Masculinity is the spine of his sound – a thread pulled taut through his discography. This is not to say his engagement with it is straightforward. At a glance – through track titles, album art, or a cursory listen – he may appear a kind of musical macho-man. This is of course, false, which is why he is successful, which is why he is interesting, which is why I am writing about him. Tzusing is compelling because his exploration of masculinity is layered, self-aware, and often satirical. Never does he simply brandish it; he stretches it, flexes it towards absurdity.

Satire, though, is rarely a stable form. To mock something, one often has to inhabit it. To parody a politician’s speech, one might perform and exaggerate their cadence or content, but this process carries a risk of misunderstanding. Hyperbolised imitation doesn’t always ensure awareness. People will find their own reflections in art, no matter how blatantly an artist lays out their message.

The idolisation of American Psycho‘s Patrick Bateman is a strong example of this. For a novel written by a gay man and a film adapted by a woman, with a script not-so-subtly pointed at the toxic machismo of Wall Street, it’s managed to attract a devoted fanbase of the very people it skewers.

What we see is that the process of translation is usually a collaborative one. If an audience fails to pick up on the joke, a message can be taken literally. There is greater risk of this in music, where a satirist’s tools are only ever sonic. Tzusing skips along this precipice with confidence.

His evolution as an artist has seen his projects grow more intricate – longer, more varied, more thematically confrontational. What has crystallised is a sound built on tension: anger cut with absurdity, elation laced with anxiety. Pain and catharsis coiled tightly around each other, but always tempered with a modicum of silliness.

His satire is effective, because, for all its weight and muscle, his music always foregrounds the weird, the wacky, or the wickedly funny. There is an inescapable playfulness in each song. Yet there remains, behind the acidity, something personal, dislocated, unresolved. A biting wit, sparked from pressure. A sense of humour forged across continents, moulded by clashing codes and overlapping identities, a tension which drives each beat. Just as to label him a simple macho-man would be reductive, to assume he is only a prankster is to deny an obvious enjoyment of masculine aesthetics. It’s in this enmeshment of critique and indulgence, satire and embodiment, where the outline of Tzusing can begin to be traced.

Building a Vocabulary; Early Experiments in Sound and Sampling

Tzusing was born in Malaysia and grew up across Singapore, Taiwan, and Shanghai. Then came the rupture: a teenage stint in San Diego under the guardianship of a religious uncle, followed by a move to Chicago, where he first started crate-digging in record shops. It’s not hard to see why dislocation is a recurring theme in his work.

Upon returning to China, he became a resident DJ at The Shelter, Shanghai’s now-mythologised basement club. It was here where his sound began to emerge:

“The first time I played Shelter during the early 2010s, I cleared the floor. I was playing a techno set, but I also played hip hop from like Dead Prez. Eventually, Gaz (club founder Gaz Williams) came over to me and said: don’t worry about it, fuck em! What club boss does that? He backed me up. So I could take a lot of chances. I also remember him telling me: If you don’t know what you are doing and you clear the dance floor, fuck you then! If you know what you are doing though, and the dance floor clears, it is not your fault. People just don’t have taste then.”

Shelter gave him a space to experiment – to push and provoke. Whilst his early releases on L.I.E.S. Records planted him firmly within the techno underground, the label now feels outdated. Over time, he has been tagged with an assortment of acronyms from EBM (Electronic Body Music) to IDM (Intelligent Dance Music, somehow less snobbish than its sister term, Braindance). All seem to cling to his catalogue, but all seem insufficient. What really cuts through is not style but stance: his music is muscular, industrial, yes, but also conceptual, thematic and rarely detached from dance music culture.

Yet Tzusing’s earliest releases don’t so much declare a thesis as sketch a mood: tension, anger, absurdity, agitation. These tracks explore sensation more than they articulate critique. The humour is there, but embryonic – folded into texture and attitude.

2015’s O.D.D. offers a glimpse into his emotional circuitry. “It’s short for oppositional defiant disorder. I found that to be really funny” he says. “To be honest, my first memory is anger. I was a pissed off kid. That never changed in a way. So, it’s super easy for me to make this anxious music. It is the easiest thing to do for me. I feel so close with this fountain of anger and hate. Making this music is always catharsis.”

One might be mistaken to assume he’s intellectualising these feelings – there’s not always distance between emotion and sound. The rebellious streak in his early music doesn’t always translate as an aesthetic choice but as the residue of experience – a channelling of feeling rather than an interrogation of it. If O.D.D. evokes aggression or anxiety, perhaps it is because it is forged from real, unresolved emotion. It’s this rawness which animates the work, which complicates any reading of Tzusing as simply a satirist.

Though in this era we also see an emergent playfulness, in both content and aesthetics. 1976 samples Network, Sidney Lumet’s black comedy about a newsreader’s on-air breakdown. Howard Beale’s signature line – “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” is hijacked by broadcasters and turned into both populist slogan and commercial product. One can almost imagine Tzusing shouting it in the studio – the track carries the same cathartic energy.

Then there’s 4 Floors of Whores, named after the local alias for Singapore’s Orchard Towers: an 18-storey building where embassies, karaoke bars, sex shops and residential units are stacked awkwardly together. It’s a vertical confrontation of diplomacy and deviance, bureaucracy and desire. The title is suggestive of a kind of sleaziness, and this is not divorced from the music. It mirrors the building’s density – an abrasive overload of noises, collapsing into dissonance. There is something pointedly masculine in how these elements clash and jostle: an architecture of overcompensation and claustrophobia. Even in his most accessible songs, there remains something of the grotesque.

This era of Tzusing’s work also marked a development of the vocal sampling which would become so synonymous with his sound. Face of Electric incorporates the ‘Kecak’, or ‘Ramayana Monkey Chant’ – a Balinese traditional dance built on collective recitations. In Flow State, Taiwanese throat singing is dragged through a current of pulsing techno.

These ‘Eastern’ elements never feel decorative. They don’t aim for smooth synthesis alongside Western forms of dance music, but provoke jagged collisions, bringing Tzusing’s dislocated experience into focus. The ancestral collides with the new; traditional forms are spliced through modern machinery. Identity is made noisy – the result is friction, not fusion – embedded at the foundation, never ornamental. Masculinity, too, is warped. These sampled voices – ritualistic, guttural, often male – tap into a register of both discipline and boisterousness. It’s the sound of muscle – the birth of his artistic vision.

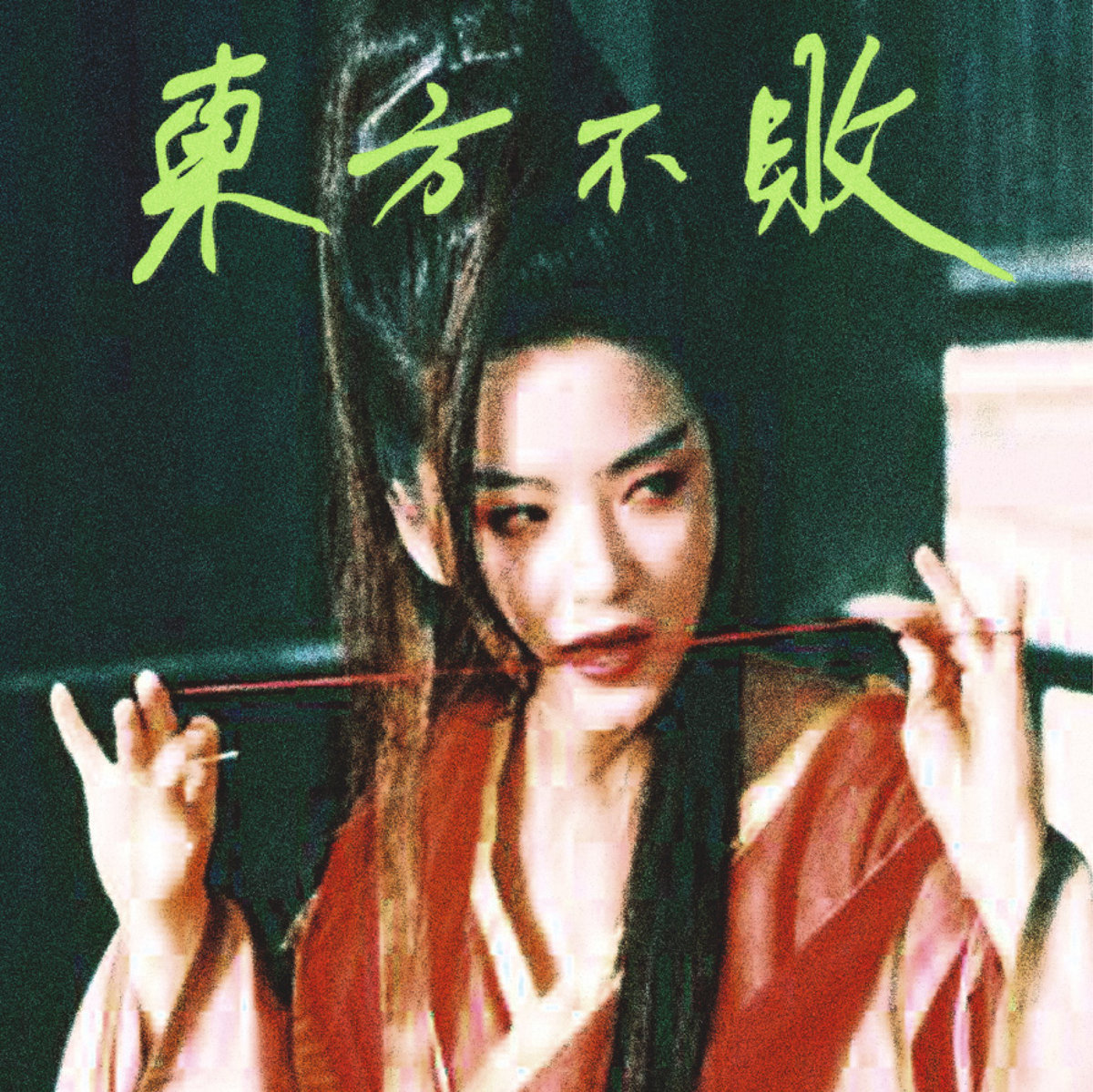

Masculine Aesthetics: 東方不敗 (Invincible East)

If Tzusing’s early releases built up a sonic vocabulary, 東方不敗 (Invincible East) was the first time he applied it to a visual and conceptual world. His 2017 debut album was the first fully-realised expression of the themes he had been circling – now sharpened into something grander and more intricate.

This shift is first marked by the heightened role of aesthetics. The album’s title sparked some misreadings upon release – mistaken by many as a nationalist slogan. In fact, it references Dongfang Bubai, a fictional figure from Jin Yong’s wuxia novel The Smiling, Proud Wanderer, whose name translates directly as ‘Invincible East’.

The character castrates himself in order to master the Sunflower Manual, a martial arts text so powerful it demands bodily sacrifice. In Swordsman II, the film adaptation from which the album art is taken, they are played by Brigitte Lin. Elsewhere, the character has frequently been represented as a trans woman. Across these versions, Dongfang Bubai’s power doesn’t come in spite of emasculation, but through it.

In an interview with Resident Advisor, Tzusing was quick to assert that there’s “something kind of badass about that”. Here, giving up conventional symbols of potency is enshrined as a new display of masculinity. Invincible East adopts this iconography not to reject masculinity but to suggest how it might be redefined.

On the opener, 日出東方 唯我不敗 (The sun rises in the east – I alone am invincible), Tzusing constructs his first truly cinematic landscape. He experiments with Chinese instrumentation – tweaking bagpipes to mimic the sharp bleat of the suona, layering the thump of tanggu drums with guzheng-like steel strings and zithers. The traditional and the futuristic, often thought of as the great collision in Chinese culture, are brought into sharp, uneasy alignment.

Esther is more brutal – a jackhammer rhythm, pounding with the blunt repetition of metal on metal. King of Hosts is more elusive, with flickering synth lines and faint Chinese dialect drifting over the backstretch of the track. Post-Soviet Models is faster and looser, buoyed by bass-heavy 808-style low toms, ringing bells and wonky melodies that worm their way through. Across its tracklist, Invincible East marked a leap in ambition and style. It was Tzusing’s most agile, varied, and thematically focused work to date – one that treated masculinity as a shifting concept to be sculpted, stretched, and reimagined.

Interlude // Notes on Performance

Once pigeonholed as a techno act, Tzusing has long since shed that skin – though not without turning off a few purists along the way. These days, his performances are more elastic and considerably harder to predict. I managed to catch him at Manchester’s The White Hotel in May 2025.

He is not a gimmicky DJ, but he does like to stretch his muscles. Whilst generally he keeps his hands busy, there is a great sense of joy to his occasional movements. His set was extremely coherent, which is not to say it was constrictive, or worse, dull. He’s a tight, precise mixer, operating within a narrow BPM window, but committed to showcasing an array of tones and genres.

He has a contagious enthusiasm for pop music. Whilst most of the focus was given to less mainstream strands of electronic music, there were grateful reactions to Corona’s Rhythm of the Night and Björk’s Army of Me, as well as remixes of his own productions Esther and Face of Electric.

Kim Laughton’s visuals were equally entertaining. Projected behind Tzusing was the relentless nodding of a distorted head, stretching and contorting in part-nightmarish, part-hilarious fashion. It felt like some semi-affectionate trolling, perhaps a mirror to those who might have overestimated their tolerances, a nod to the strange, straining joy of the rave, or most likely, a reminder of my bad dancing.

绿帽 Green Hat; Repression and Fragility

Tzusing’s sophomore album is more violent, more emotionally volatile, and wider in scope – taking aim at the broader implications of conventional masculinity. This time, the satire is sharper, the humour, more cutting, the sound, more explosive.

The album’s title is explained by a text-to-speech voice listing common cultural missteps tourists make in China. Among them: wearing a green hat, described as “the Chinese symbol of a cuckold”. The notion traces back to Tang Dynasty folklore. Li Yuanming, a travelling scholar, had a wife named Cifu, who grew lonely in his absence. To signal to her lover that it was safe to visit, Cifu wore a green hat. The symbol now carries deep cultural implications – so much so that buying a green hat in China is notoriously difficult. A marker of humiliation and the fear of losing control, it becomes the perfect image for Tzusing’s most recent confrontation with masculinity.

In an interview with The Quietus, Tzusing revealed, “I semi-went with this concept because I thought it would piss off my dad, and it did. I told my dad, ‘This is the name of the album’, and he was like, ‘What the fuck!’ I didn’t tell him that it was because I knew it would piss him off, but he has this very rigid idea of what it means to be a man. This Chinese man’s fear of this thing, of this hat and what it symbolises, is interesting to me. There’s this pretence that the masculine façade will be cracked if your girlfriend sleeps with someone else, that it will make you less of a man. It’s like kryptonite, it’s this really scary concept to a lot of Chinese men”. Above all, it is the concept of repression that feels central to this album – the fragility of masculine performance when anxiety and shame take hold of the mind.

The album art is beautiful. It features two strikingly masculine images: one of Tzusing wearing the green hat, blood streaking down his ear; the other, topless and seemingly baptized by the same emblem. As with his use of Dongfang Bubai, Tzusing carves masculinity out of emasculation whilst questioning how we define both. There’s a theatrical quality here – Tzusing performs ‘shame’ with such commitment and assurance that it begins to register as dominance.

The music reflects this tension. The album is kickstarted by 趁人之危 (Take Advantage). Here, Tzusing samples the infamous ‘I Drink Your Milkshake’ speech from There Will Be Blood. It’s a clever inclusion – after all, few figures embody comical masculine ego better than cinematic arch-capitalist Daniel Plainview. His slurps enter the soundtrack in a display of uncomfortable ASMR before leading into a growling bassline. There is a ploddiness, a drawn-out quality to each beat.

偶像包袱 (Idol Baggage) leans more heavily on the screeching strings so unique to Tzusing’s production style. The sense of repression is thick: a rigid, mechanical consistency that struggles to keep composure whilst chaos and anxiety sizzle over the edges. It conjures this opposition between interior unease and outward performance, volatility and control – it’s intensely fragile. The track is seen out by snippets of feminine laughter, twisted into horror-movie style cackles.

Muscular Theology is aptly titled – a physical, bruising composition. Yet it also comes across as remarkably self-aware, and though dark and weighty, it’s never portentous. It’s almost absurdly muscular in places, reaching a point of exaggeration that can only feel satirical. The physicality is paired with odd, playful sampling. Deep chants are interspersed by frog ribbits and strange pre-drop lines.

These moments are where Tzusing is most piercing and most funny. On Balkanize, there are monkey noises and whiny F1 car squeals. Clout Tunnel is adorned with samples from first-person-shooter game Apex Legends. His sampling manages to extract such peculiar staples of masculinity, isolating the absurdity embedded within them.

The tempo rises as the album progresses. Exascale draws from jungle and footwork, its flanged percussion warping in different directions whilst steady rumbles of bass maintain weight and heft. Residual Stress is an effective closer. Patterns of clapping are peppered throughout with flourishes of deep grunts and rapid-fire machine gun spray.

With 绿帽 Green Hat, Tzusing sharpens his lens, tracing the bleed of machismo into all aspects of culture, from politics to gaming, folklore to family dynamics. It raises up the anxiety and the humour whilst dancing assuredly along the fine discriminations of satire and sincerity.

Outro // Final Thoughts

Is Tzusing dismantling the master’s house with their tools, or simply performing inside it? Clearly he is fixated on hypermasculine aesthetics – militaristic motifs, brute rhythms, mythologies of dominance.

Crucially, I think, Tzusing’s music probes the brittle edges of masculine pride: the fear of failure, the terror of exposure, the fragility behind the façade. He doesn’t seek to resolve that fragility – he lets it pulse through every texture. In doing so, he reshapes the boundaries of what we recognise as ‘masculine’. The weird and the eerie, the camp and the silly, are exo-skeletoned with physicality and purpose. They become as much masculine symbols as the oiled muscles of patriarchy. Just as his artwork conveys, the abandonment of one’s socialised masculinity can be a powerful thing indeed.

I suppose this is the line people can miss – the horseshoe of gendered performance. The louder and tougher the posture, the more compensatory it tends to be. Sometimes the more joyful the rejection of convention, the more assured the self beneath.

Tzusing doesn’t outright reject normative masculinity but he lays bare its contradictions. As we look to a landscape so burdened with the dullness of male ego, so exploited by stiff repression, what better way to deride and dismantle than to show how masculinity can also be so very fun?

Featured Image Credit: Sean Marc Lee

Leave a comment